Why gold’s 2025 rally might say more about psychology than policy

Gold’s rally isn’t just about inflation or fear — it’s about what happens when gold becomes both insurance policy and identity. Cue the 'Veblen' theory.

After softening somewhat during the course of the US government shutdown, precious metals jumped again this week, on news the same government might finally reopen. Gold hit $4,110 on Monday, with silver over $50. Analysts at J.P. Morgan see gold climbing to $5,200 or $5,300 by 2026, led by relentless central bank buying.

China, Turkey, and Poland are all converting surpluses into metal. The stronger the dollar’s shadow grows, the more nations seek the glint of autonomy. As John Rubino told Collapse Life last month, we may be witnessing the early stages of a fiat-currency “death spiral.”

Most major governments are now caught between unsustainable debts and political paralysis. Their interest costs are rising faster than their ability — or desire — to cut spending, creating what Rubino called a “debasement trade”: capital flowing out of paper promises and into tangible stores like gold, silver, and farmland.

Rubino’s argument helps explain why central banks are still buying at record levels even at $4,000-plus prices. The world’s monetary managers are hedging against their own system. “So what’s happening lately is that the value of the dollar is falling dramatically,” he says. “And we’re seeing that in the price of gold because the dollar number we assigned to gold is going up. But it’s not because gold is doing anything. It’s because the dollar is doing something very bad.” In other words, gold’s rally isn’t about exuberance — it’s about the fact that when the measuring stick itself is shrinking, every ounce looks larger.

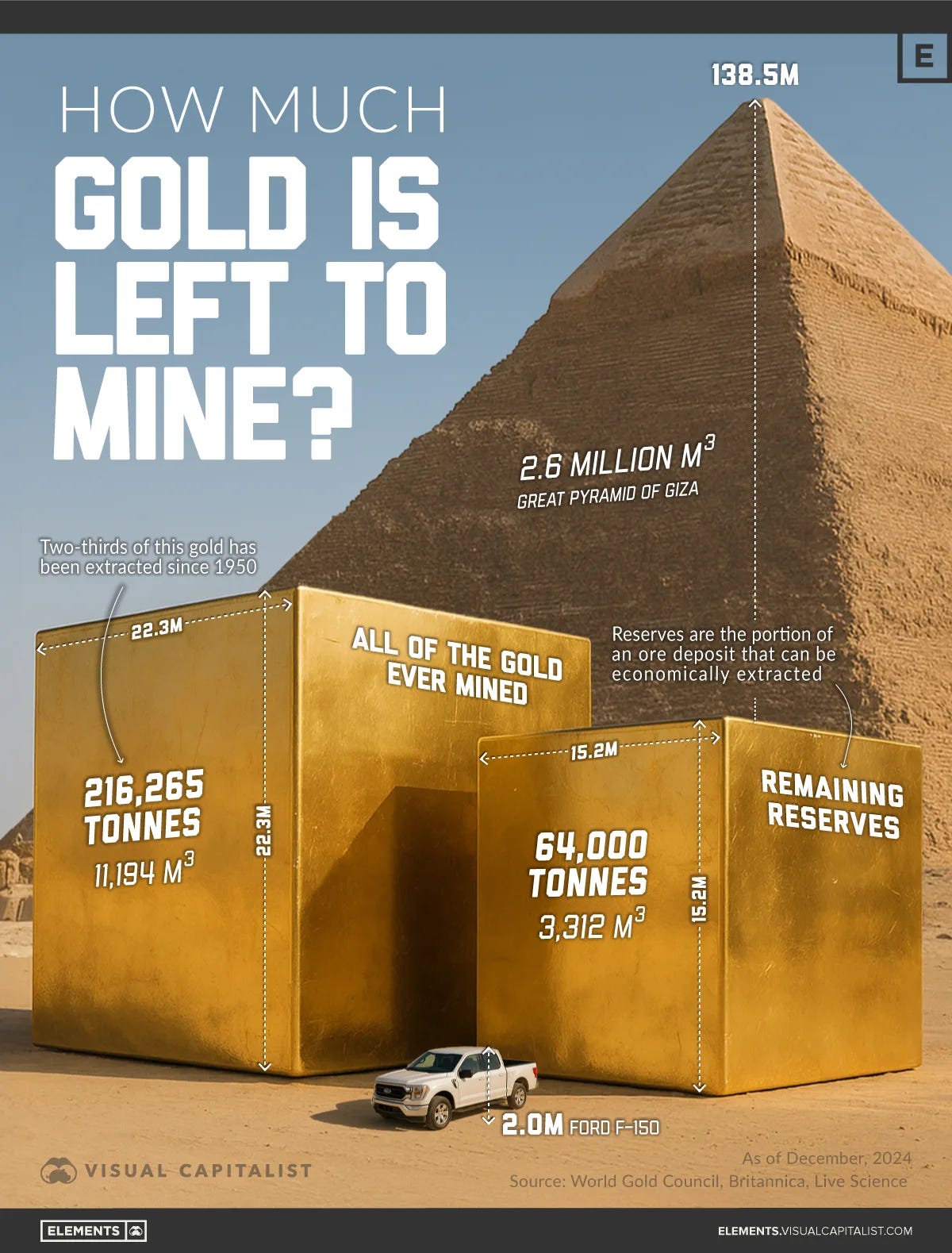

Part of gold’s mystique lies in its physical limits.

As Visual Capitalist recently illustrated, if every ounce ever mined were melted together — about 216,000 tonnes — it would form a cube only 22 meters tall, roughly the height of a four-story building. All the world’s remaining, economically recoverable reserves amount to just another 64,000 tonnes, a smaller cube just 15 meters high.

Nearly three-quarters of Earth’s known gold has already been pulled from the ground and two-thirds of that happened after 1950, during the great industrial acceleration. So, perhaps the idea of scarcity is feeding gold’s climb. The less there is to find, the more we seem to want it.

But before we read too much into gold’s current rally, it’s worth remembering what Bob Moriarty told us recently: human beings are herd animals — and they’re mostly “dumb as bricks.” (Gosh, we love Bob for his irascible, irreverent truth!)

Contrarians make money, Moriarty reminds us; when everyone’s buying the contrarian sells. Likewise, when everyone’s selling the contrarian buys. Moriarty has been around the block a few times so when he says sentiment, not logic, drives markets, we listen .

He pointed out that gold has already multiplied roughly 125-fold since the early 1970s. Every necklace being hocked in New York’s Diamond District today is being unloaded at a profit, while every gold bar bought in Amsterdam this week is being purchased at an all-time high.

So, if we’ve got rational sellers and irrational buyers is that a sign that gold might have become a ‘Veblen good’ for consumers, where the higher the price, the more its possession signals power? More on that later.

Neither Rubino nor Moriarty dismiss gold’s long-term strength. Moriarty simply warns about timing: “When gold goes up nine weeks in a row,” he told us, “there’s an extraordinary amount of bullishness — and typical investments go down after that.”

The risk, in other words, is the mania and not the metal itself.

Still, something deeper is happening as central banks continue to bet against old systems and stack more gold. It’s not just a financial move… it’s also symbolic. Yes, they are building their reserves, but also their prestige. Each ton they add to their vaults is a declaration of independence from a jaded global system that no longer has the trust or authority it once did.

At the sovereign level, gold does appear to have become a ‘Veblen good.’

The term comes from Thorstein Veblen, a Norwegian-American economist writing at the dawn of the 20th century. In The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899), he coined the well-known term “conspicuous consumption” to describe how elites buy goods not for their utility but for the status they confer. A ‘Veblen good’ defies the normal laws of supply and demand: its desirability rises as its price goes up simply because the price itself is a symbol of its worth.

Today, the Veblen effect doesn’t stop with central banks. It’s creeping into consumer behavior too. As Moriarty points out, it’s perfectly rational to sell when prices are high and utterly irrational to buy. But, it could be that at least some buyers are not doing so because they fear monetary collapse. It could be that they’re simply responding to social proof. When headlines blare “record highs,” gold becomes aspirational. Owning even a few grams feels like participation in something elite and exclusive.

In Asia, this psychology merges with tradition. Indian families measure stability in the number of bangles, not bonds. Chinese consumers buy 24-karat coins for newborns because they trust continuity more than credit. As price hikes amplify demand, scarcity and prestige reinforce each other until the object’s price becomes its proof of worth. That’s a textbook Veblen pattern.

Yet, as Moriarty reminds us, that logic can flip fast. When everyone rushes to join the herd, the herd walks off a cliff. So, we find ourselves in a contradictory moment: retail sellers in Manhattan cashing in at 125× gains, central banks hoarding as fiat credibility erodes, and nervous consumers buying at record prices because everyone else is.

Each group can justify the reasons for their actions, but everyone’s bet is not going to pay off at once.

Gold’s rally tells two stories. One is about macro policy and declining trust in debt-based money. The other is about psychology — the desire to belong to the winning side of history, even if that side is built on the fear of collapse.

Moriarty likes to say sentiment is the only thing that moves markets. Maybe so. But sentiment is just another form of confidence — and confidence, once spent, is harder to replenish than gold itself.

Thanks Susan :) not enough money to buy gold, no gold to sell so I am all good!