2026, a space oddity: 'the cloud' in orbit

Why moving AI data centers into space won’t save the planet — and may make conflict, debris, and systemic risk far worse.

On February 2, SpaceX, the rocket and satellite maker, acquired xAI, the artificial intelligence company. The news was posted in a memo penned by Elon Musk on the SpaceX website, with the headline: ‘xAI joins SpaceX to Accelerate Humanity’s Future.’

The first paragraph of the memo must be read to be believed (emphasis ours):

SpaceX has acquired xAI to form the most ambitious, vertically-integrated innovation engine on (and off) Earth, with AI, rockets, space-based internet, direct-to-mobile device communications and the world’s foremost real-time information and free speech platform. This marks not just the next chapter, but the next book in SpaceX and xAI’s mission: scaling to make a sentient sun to understand the Universe and extend the light of consciousness to the stars!

The merger is reportedly valued at around $1.25 trillion, according to Bloomberg, and a key driver appears to be Musk’s obsession with developing orbital data centers powered by AI satellites.

“Current advances in AI are dependent on large terrestrial data centers, which require immense amounts of power and cooling. Global electricity demand for AI simply cannot be met with terrestrial solutions, even in the near term, without imposing hardship on communities and the environment,” Musk wrote in the memo.

Hey, that sounds like a pretty responsible attitude, doesn’t it?

Musk also outlined plans for a massive constellation of one million satellites to host these “space-based” data centers, leveraging continuous solar power in orbit and SpaceX’s capacity to deploy hardware at scale.

The concept itself isn’t entirely novel. Big Tech firms, including Blue Origin, Google, and Open AI, have explored space-based computing ideas for years as a way to relieve the mounting energy, water, and land constraints of terrestrial data centers. But moving data centers into orbit raises a different class of questions — about unintended environmental consequences, governance, conflict, and the fate of stranded infrastructure once things go wrong.

Musk’s pitch is that orbital data centers offer an upside because they run on continuous solar power, avoiding fossil-heavy grids and water-intensive cooling systems. If powered entirely by sunlight in space and not beaming energy back to Earth, the waste heat they generate would radiate into space rather than accumulating in Earth’s atmosphere. From a purely abstract perspective, that might be framed as a climate win, if you’re into that sort of thing.

But that framing rests on a critical assumption: that orbital data centers would replace land-based infrastructure rather than simply adding another layer of computing capacity. However, if space-based AI data centers come online, they are far more likely to augment terrestrial data centers rather than supplant them completely. The result wouldn’t be fewer servers on Earth, but more servers everywhere, particularly in jurisdictions where oversight is weakest. In that scenario, orbital data centers don’t relieve environmental pressure; they normalize perpetual expansion under the banner of efficiency.

Any purported upside, therefore, comes with significant caveats.

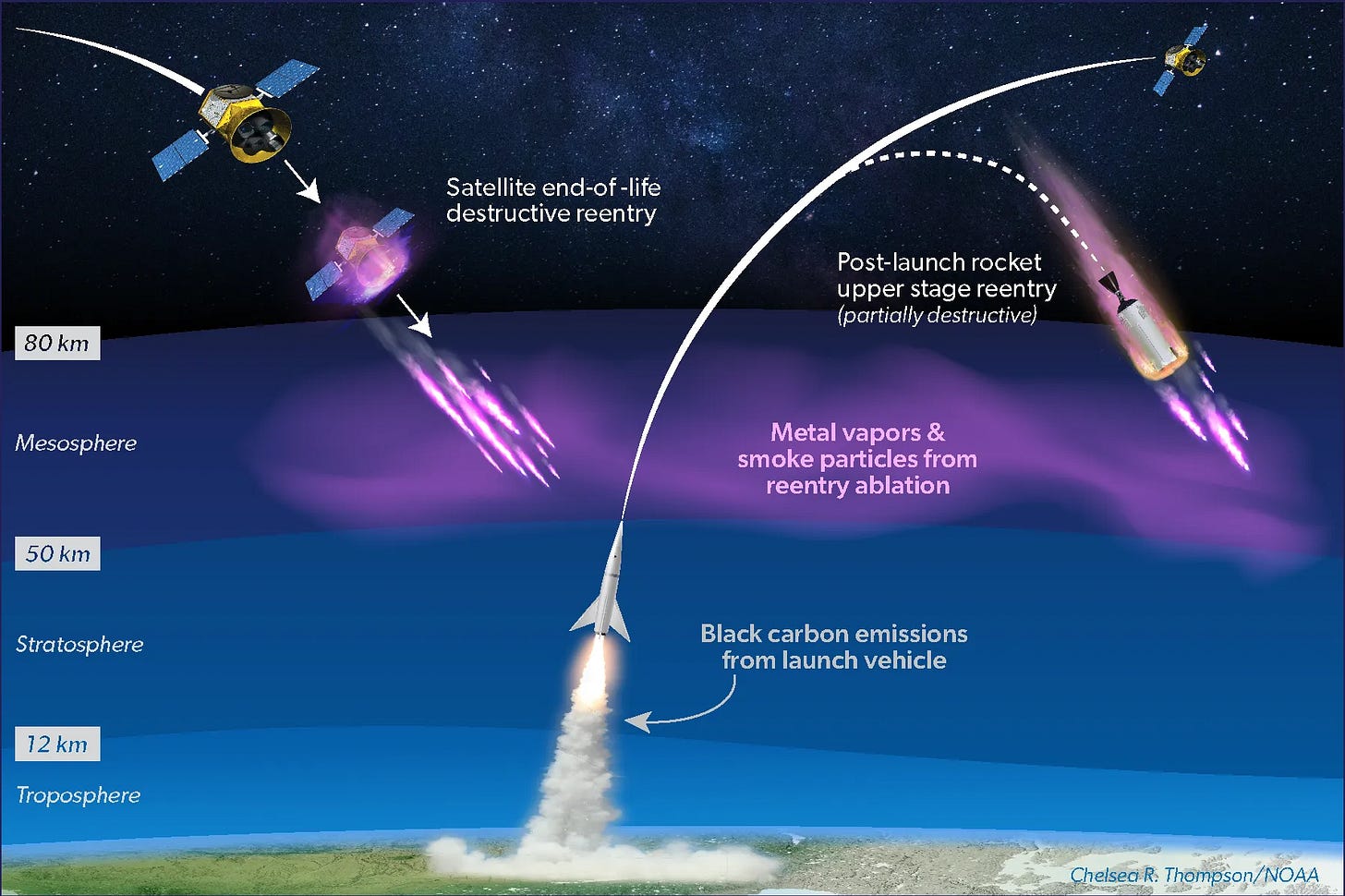

To begin with, launching satellites into orbit is bad for the environment. Rockets emit pollutants during ascent, and when satellites reenter the atmosphere, they burn up and release aluminum oxide and other metal particulates which precipitate out. Researchers from University College London say mega-constellation launches have led to a threefold increase in soot and carbon dioxide and these particles stay in the upper atmosphere much longer than Earth-bound sources, creating 500 times the climate warming impact of soot from aviation or ground-level sources.

Recent modeling by NOAA and researchers published in the Journal of Geophysical Research suggests that large-scale reentry from mega-constellations could inject enough “alumina in the stratosphere to alter wind speeds and temperatures at the poles and impact Earth's climate in ways scientists don't fully understand.”

Then there’s the physical footprint on Earth that building space-based data centers requires: mining and refining critical minerals, fabricating chips, manufacturing launch vehicles, and operating ground stations. Shifting servers into orbit doesn’t eliminate those impacts; it just adds rockets and exotic space hardware on top of them.

So even if some pressure were relieved from land-based power grids or water tables, the tradeoff would be the creation of a new category of high-altitude emissions that are poorly regulated and only partially understood.

Light pollution and radio interference compound the problem. Astronomers and climate scientists already struggle with the effects of existing satellite constellations on Earth observation, hazard monitoring, and basic scientific research. Adding more reflective and radio-emitting hardware to low Earth orbit for AI data centers would intensify those disruptions.

From the standpoint of regulation and data sovereignty, orbital data centers sit squarely in a legal gray zone — and that ambiguity is likely not accidental. Under the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, the “launching state” or state of registry retains jurisdiction and control over space objects, regardless of where they operate. Ownership doesn’t change simply because hardware is in orbit. But jurisdiction in space is far fuzzier than, say, a data center located in Oregon, subject to US federal law, state regulation, and foreign privacy regimes like the European Union’s GDPR.

That fuzziness creates obvious incentives. Companies seeking to evade data localization requirements, strict privacy protections, or emerging AI safety rules can simply choose more permissive launch and registration states, or run sensitive workloads on orbital hardware nominally governed by laxer jurisdictions. Even when regulators determine that an activity violates the law, physically inspecting or seizing space-based infrastructure is much harder than raiding a terrestrial facility.

In a militarized conflict, disabling an adversary’s orbital data centers through cyberattacks, signal jamming, or anti-satellite weapons would be an obvious strategic objective. Once embedded in mega-constellations, these systems stop being neutral commercial infrastructure and become tempting military targets.

The danger is that attacks in orbit don’t stay contained. A successful strike doesn’t just knock out a single system; it generates debris that threatens every satellite sharing those orbital shells. By entangling everyday cloud services and commercial AI workloads with strategic military assets, orbital data centers blur the line between civilian and military infrastructure. That raises escalation risks on Earth as well as in space, as attacks on commercial systems can be interpreted as acts of war.

All of this feeds into the already dire problem of space debris. Massive orbital data-center constellations are almost perfectly designed to worsen it. We already talk about “stranded assets” when oil pipelines or coal plants are phased out. In orbit, stranded assets are far more dangerous.

When satellites lose propulsion or remote control, they can’t maneuver or deorbit. They drift across orbital paths, collide with other objects, and turn functioning infrastructure into cascading hazards. The video below from LeoLabs gives a real-time view, as of February 2, 2026 at 23:32 UTC, of debris in low Earth orbit, which currently hosts more than 11,000 active satellites.

SpaceX’s Starlink constellation alone reportedly executed more than 140,000 collision-avoidance maneuvers in just the first six months of 2025. Now imagine adding thousands more orbital data-center satellites, some positioned only a few hundred feet apart. A single failure or impact could fragment a satellite into thousands of pieces, threatening neighboring units and triggering a chain reaction that wipes out entire clusters.

At that point, stranded assets don’t just represent lost capital. If a data-center mega-constellation were to fail catastrophically — and there is no reason to assume it wouldn’t — the consequences could ripple through AI and cloud services that finance, logistics, healthcare, education, travel, and governance have quietly come to depend on, triggering cascading failures on Earth.

Elon Musk and fist-bumping Big Tech bros will cash in on this latest expansion just as they have on previous waves of extraction and enclosure. Like the Spanish Conquistadors, the costs of their endless conquering — environmental, geopolitical, financial, and systemic — will be paid later and most certainly not by them, but by the people who inherit a permanently degraded orbital commons with few, if any, options to repair it. Their sole mission is to go for the gold; the rest of us can go to hell.

Strong piece. The key insight is that orbital datacenters probably wont replace terrestrial ones but just add another layer of expansion, which totally changes the environmental math. I've been watching the debris issue escalate for awhile and the Kessler syndrome risk with densely packed satellites is genuinely terrifying. The legal ambiguity around jurisdiction is also slick, companies can essentially launder regulatory oversight through permissive launch states.

What could possibly go wrong 😱