Where did the water wars go?

The conflict over water hasn't gone away. It's just morphed into control over a commodity — and the reins were handed to corporations.

In April, a brief clash flared along India and Pakistan’s ‘line of control.’ For a frightening few days, the specter of war between two nuclear powers gripped the headlines. Military tensions have now cooled, but another conflict still quietly unfolds: water.

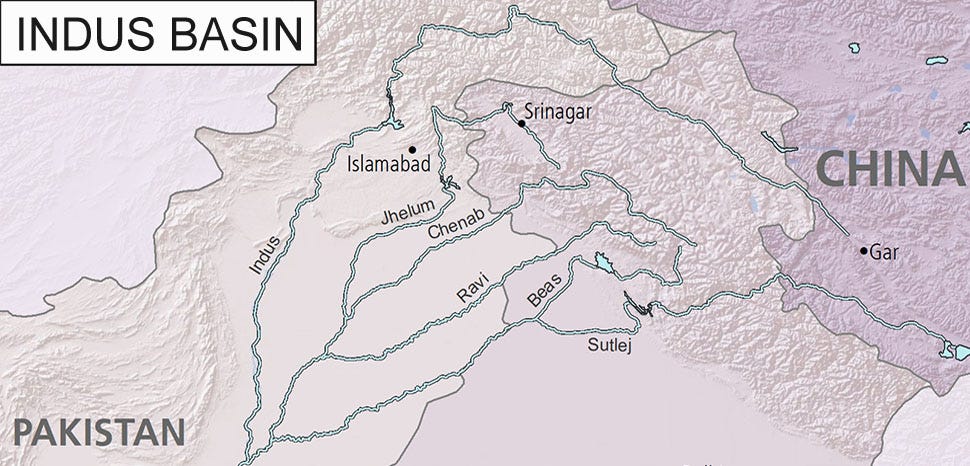

For over six decades, the Indus Waters Treaty, brokered by the World Bank in 1960, stood as a rare success story — surviving skirmishes between two fractious neighbors and splitting a complex and critical six-river system: India got the eastern rivers, Pakistan the western ones.

That delicate arrangement is now fraying. India is moving forward with dam and diversion projects that, while technically allowed under the treaty, are seen by Pakistan as provocations.

This isn’t just a South Asian issue. Globally, water is a tool of power and profit.

In the occupied West Bank, Israel controls the spigots and uses water as a weapon. After Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, Ukraine blocked the canal supplying 85% of the peninsula’s fresh water. Even in North America, water spells trouble. A 1944 US-Mexico water treaty is under strain as drought grips the Rio Grande and Colorado River basins and farmers on both sides of the border struggle to survive.

An ancient Babylonian conflict over control of the Tigris River is widely considered history’s first war over water. The Pacific Institute, a leading voice on water and security, has compiled an open source database tracking nearly two thousand instances where water was a trigger, a casualty, or a weapon of violent conflict. Last year, the Institute reported an increase in violence related to water resources.

Here’s what’s less examined: how much of this water-related strife is not organic, but instead, engineered — the result of external forces manipulating water systems for profit, leverage, or political control.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, as the threat of water wars dominated headlines and the United Nations predicted looming crises, international finance institutions like the World Bank and IMF began pushing market-based solutions: privatize water, price it accurately, and deliver it using private firms. Developing countries seeking financial assistance often had to agree to implement structural adjustment programs that included the privatization of water as a condition for receiving loans. Billions flowed into projects that generated debt and locked nations into long-term repayment.

Suddenly, the rhetoric claiming that the next global war would certainly be over water began to soften: "water scarcity" became "water management." "Crisis" turned into "investment opportunity." The threat of wars for water didn’t vanish — it just moved off the battlefield and into the boardroom.

Water scarcity was reframed as a technical problem with a technocratic solution. Governments — people — couldn’t manage water resources efficiently or honestly. Too much was lost to waste and theft. Leave it to the experts to solve the problem through policy reforms, new billing systems, and a profit incentive.

Companies like Nestlé and Coca-Cola extracted groundwater, bottled it, and sold it back at a markup. European water giants like Veolia, Suez, and Thames Water grabbed contracts worldwide, often leading to price hikes and service cuts. Dams, pipelines, and desalination plants became cash cows for firms like Bechtel and Black & Veatch, usually under “public-private partnerships” that used government money to build infrastructure, socialized the risks and pitfalls, but privatized profit.

In 2000, a subsidiary of France's Veolia, the world's largest water services provider, took over the management of water resources, water treatment and distribution, and wastewater and stormwater evacuation for Bucharest. In 2015, Romanian prosecutors accused the corporation of paying out over €12 million in bribes and driving up the consumer price of water by 125%.

In 1999, one year after Bolivia agreed to an IMF loan of $138 million that required privatization of public enterprises, the government signed a $2.5 billion contract to hand over the municipal water system of Cochabamba to a multinational consortium of private investors, including a subsidiary of the US-based Bechtel Corporation. The new company hiked water rates and even took over drinking water systems and irrigation systems that had been built by communities themselves, and demanded that these new “customers” start paying to use their own water systems. When prices tripled, protesters shut down the city for four days, going on strike and erecting roadblocks throughout the city. The protests eventually led to a re-nationalizing of water in Bolivia and ushered in the election of Evo Morales in 2005.

As these examples show, the fight over water never went away. It was absorbed into the system — into contracts, treaties, hedge funds, and corporate reports.

Water is now a battlefield, a business, and a bargaining chip — all at once.

The free market system has, without a doubt, proven to be most effective at spurring innovation, driving efficiency, and encouraging entrepreneurship and — by extension — freedom. What we are witnessing however — not just in water, but across the spectrum — is a perversion of that system. What should be ever-improving spurred by supply, demand, and broader market forces is instead gamed by elites who have commandeered government coffers and melded it with private industry. To their sole benefit.

In the past, attempts to achieve this were interrupted. Benito Mussolini pined for fascism as the ideal form of autocratic government. We know how that ended.

What’s different today however, is that Silicon Valley technocrats are the new high priests of the ‘fourth industrial revolution.’ Their access to all the data, combined with the marionette strings they pull (for now) on artificial intelligence being forced on us all, gives them unprecedented control. Thus, they see control over the interaction between government and industry as entirely their purview, rendering the rule of law, the mechanics of state, and the vast majority of people (too poor, too asleep, or too naive to see their coming enslavement via the embrace of technological convenience) as entirely their birthright.

One of our favorite substacks, Doomberg, often acknowledges that “energy is life.” They’re not wrong, in a modern, industrial society sense. However — and this will come as no surprise to anyone who knows biology — water is actual life. Without it, we perish. The privatization of water into the hands of destructive, nefarious, private forces who may very well see many of us as expendable, is surely a sign we are headed toward an epic and ultimate battle for freedom and for existence.