What America can learn from Nordic countries about prepping

Why does Sweden empower its citizens to ready themselves for emergencies, while America mocks those why try?

In Sweden, millions of households recently received a government-issued pamphlet entitled: "In Case of Crisis or War." The practical guide to surviving emergencies contains advice on everything from stockpiling long-life foods to preparing for a week without power.

The information booklet is part of a long-standing tradition in Nordic countries where citizens are encouraged to take collective responsibility for readiness. Finland, Norway, and Denmark have similar campaigns, which effectively normalize preparedness as a civic duty.

Contrast this with the United States, where mainstream media and academia often cast anyone with a preparedness mindset as a fringe character — a doomsday prepper, right-wing extremist, tinfoil hat wearer, or religious zealot awaiting the apocalypse. This dismissive attitude not only stigmatizes a practical outlook, but also reflects a deeper cultural and institutional failure.

In Nordic countries, preparedness is framed as a shared societal responsibility. The Swedish pamphlet explicitly states, “If Sweden is attacked by another country, we will never give up,” reinforcing both resilience and solidarity. In America, the picture is different. Preparedness is treated as an individual responsibility — a commodity to be purchased rather than a skillset to be shared.

Some scholars have dubbed this phenomenon “bunkerization,” emphasizing an isolationist mentality over community. However, Americans end up relying on their own wits because they know FEMA might not show up on time — if at all. Look no further than the relief and recovery efforts in North Carolina if you need a recent example.

Why is preparedness stigmatized in the US? The same country that glorifies rugged individualism paradoxically mocks those who act on that ethos. Preppers are caricatured as paranoid and out of touch, despite FEMA’s own recommendations to stockpile 72 hours’ worth of food and water.

The stigma obscures the practical roots of readiness. Just as Nordic governments remind their citizens that emergencies are inevitable, prepping in the US should be seen as rational. After all, hurricanes, wildfires, earthquakes, flooding, and infrastructure failures aren’t theoretical in America — they’re annual events.

The real problem lies deeper. The fact that Nordic countries are running preparedness campaigns reinforces the idea that their citizens still trust institutions and have a shared sense of responsibility. Here in the US, where public trust is in tatters and we’ve been taught to hate each other, preparedness has been privatized.

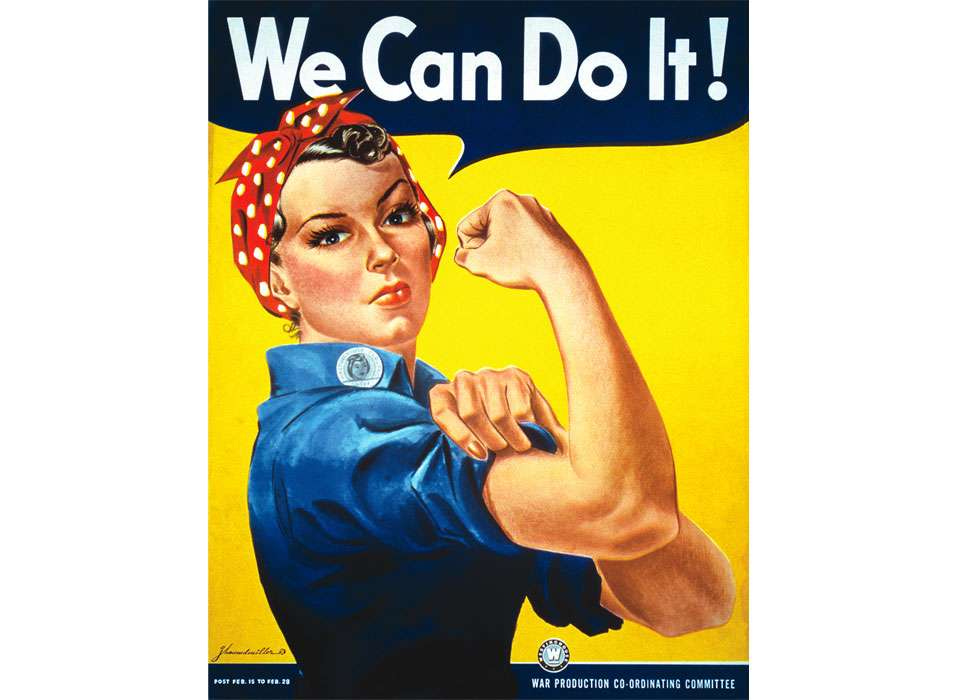

During World War II, the US government mobilized Americans through extensive public campaigns, rationing programs, civil defense initiatives, and workforce training. Messages of unity and shared sacrifice were conveyed through posters, media, and education, while programs like Victory Gardens and war bond sales encouraged direct participation. Communities prepared for emergencies through civil defense drills, and "Rosie the Riveter" brought women into the workforce. This nationwide push fostered a sense that readiness and resourcefulness were essential tools for overcoming large-scale crises.

Now, Americans are left to navigate disaster readiness through consumerism, purchasing their security in the form of Ring cameras, emergency food buckets, and standby generators.

Recent approaches to preparedness in America, like the post-9/11 “If You See Something, Say Something” campaign, focused heavily on public vigilance but ended up fostering a culture of distrust and fear (not to mention over-the-top Karen-ism!). This reactive strategy prioritized individual responsibility and undermined trust in institutions and communities.

Fast forward — by the time COVID-19 landed on our shores, measures like social distancing, mask-wearing, and vaccination were seen through a lens of doubt. Sweden, by contrast, took a measured approach and was one of the countries whose institutional reputation (around the lockdowns, anyway) emerged unscathed.

Readiness isn’t about paranoia or ideology — it’s about practicality. By shedding the stereotypes and recognizing preparedness as a logical response to real risks, Americans can reclaim a mindset that values independence, capability, and foresight. Preparedness isn’t a sign of fear — it’s a sign of strength — strength to face uncertainty with confidence, just as past generations of Americans did when the stakes were highest.

Being prepared is completely rational! Your points about how this has become stigmatized in this disconnected-from-reality culture are spot-on. I grew up in rural/small town America, and being prepared is just what you did. Farm families have typically had a large pantry, stored supplies, a root cellar or something akin to that. My grandpa's farm was totally self-sustaining, and they always had a supply of stored food because you never knew what disaster or crop failure might happen.

While I get that this was awhile ago, the reasons for being prepared haven't changed. In fact, I believe it's more important than ever. Between an aging power grid that needs a lot of work, the increasingly severe weather/flood/fire disasters, or whatever political bs might blow up (and curtail shipping), having at least a couple of weeks worth of non-perishables and clean water on hand is really smart. There's nothing nutty or crazy about having the wisdom to plan ahead for the unexpected! If you have a family or loved ones (including animals), it's a must.

I live in southern Appalachia, the mountains of Western North Carolina. At the end of September, Helene hit, and devastated our region. Way beyond what anyone ever believed could happen here. Some counties worse than others for sure, but generally bad everywhere. There was a lot of damage on my property, but fortunately my old log house held up pretty well and my growing areas were okay. But I had no power for 10 days. Others fared worse.

Initially after the storm, stores were closed because they had no power, many roads were impassable, you couldn't get gas, etc. I have my own well, but my pump is electric, so... Clean water was an immediate need. Fortunately I had already stored gallons of water, which I had been in the habit of doing in case of outages. 3 weeks of water. I also had many cans of beans, peanut butter, and 6 jars of dry roasted peanuts. As well as dehydrated apples from this year's apple crop. Several boxes of oat cereal, a couple canisters dried oats. What I do is record the date the things I store, then gradually use them then replace with newer over time. This way nothing goes bad if it's not needed, but there's always something on hand should there be an emergency. (I also have a small Coleman camping stove which I used on the porch to boil water).

FEMA got here relatively quickly, with water and food, but the bigger problem was local governments who were not prepared for this event. The people in remote mountaintop locations had bigger issues because no one could get to them. But again, this truly was unprecedented for us. Another issue was we didn't have cell service, internet/routers, etc, so my radio was lifeline to what was going on, and finding out where supplies were being given out so I could share that info with my neighbors. People came together and really helped each other, which is probably something you don't see a lot of in urban areas.

FEMA was getting money to most applicants quickly, and I got initial aid money within 3 days of applying, as did all my neighbors who applied for help. But one thing I learned during the aftermath of this storm is never be without at least some cash on hand because the banks were closed and teller machines didn't work. The gas stations and stores that opened first were only taking cash.

I think people have the tendency to go along in their lives and just assume that nothing is going to drastically change - the stores will always be open, they will always have food, there will always be water coming out of the tap. It's kind of that normalcy bias we all tend to have.

But things can change in the blink of an eye, and while you may have some warning in some cases, other times you may not.

To me, doing what you reasonably can in order to prepare for emergency situations is basic common sense. And planning ahead is what you do when you're a grownup! A culture that is so adolescent and immature to mock those who do, well, that's a culture that's going to be in a lot of trouble in the years ahead.

I think that there are some real differences in the way that the mentality of the average US citizen is directed to be focused.

First of all, we are not supposed to be focused on ourselves or our family. We are supposed to have our jobs as our main priority. That way we can be docile consumers.

Next is the idea that we are supposed to leave everything to the government to take care of us. Of course they are clueless. For instance, in the event of a disaster, they want to order everyone to evacuate. OK. To where? With what money on hand? With what transportation? No, it is just an ambiguous, "Well, go somewhere else." Look no further than the way that they handled hurricane Katrina in New Orleans. They had no idea what to do with the people who were unable to evacuate.

The ideas that they come up with for dealing with emergencies are all focused on what people do in big cities. How do you store several weeks worth of food when you live in a closet sized apartment in NYC when you don't even have the space for a spare jacket?

Now to be fair, a lot of the preppers are a bit on the fringe. I watch some of the prepper videos and there are a lot of them that would be hard pressed to spend an overnight camping trip to a state park.