The decline of reading is not about nostalgia

What looks like a harmless cultural shift may be a warning about who retains the tools of judgment — and who doesn’t.

One hundred years ago, a large portion of the adult US population could not read at all or only haltingly. Literacy levels in the 19th and early 20th century were shaped by class, race, geography, immigration status, and access to education. You could still get by without reading or writing, but it put you at a disadvantage. If you wanted to understand a war, a labor strike, a land dispute, or a ballot initiative, you had to engage with the printed word.

By the late 20th century, the United States reached something of a golden age in reading culture. Literacy rates were soaring and print still dominated the landscape. Although television was ubiquitous, it was scheduled and limited; outside of the few prime time evening hours on three networks there wasn’t much to hold a person’s interest for long. The internet had not yet fragmented our attention spans, which meant reading a novel, a newspaper, or a magazine was a very normal thing to do.

Now, just over a quarter of the way into the 21st century, reading is (to put it bluntly) dying. The problem is not that people can’t read. It’s that reading has become optional, and optional practices tend to atrophy when the environment is optimized against them.

A recent study using data from the American Time Use Survey (2003–2023) found that the proportion of Americans who read for pleasure on an average day dropped about 40% in those years. Another survey from 2025 found that 2 in 5 American adults did not read a single book (print, digital, or audio) last year.

Educators are seeing the consequences. College instructors report students who struggle to read a paragraph independently, not because they lack intelligence, but because they lack stamina and training in sustained attention.

“It’s not even an inability to critically think,” Jessica Hooten Wilson, a professor of great books and humanities at Pepperdine University told Fortune. “It’s an inability to read sentences.”

Expectations are quietly being lowered out of necessity. “I feel like I am tap dancing and having to read things aloud because there’s no way that anyone read it the night before,” Wilson admitted. “Even when you read it in class with them, there’s so much they can’t process about the very words that are on the page.”

Every era trains people for the world it expects them to inhabit. The print era trained people to be patient, spend time with their imagination, and inhabit other made-up worlds using their cerebrum. Our current era trains people visually, encouraging them to react quickly, seek constant novelty, and trigger certain behaviors. Does that make people stupid or does it simply optimize them for a system that no longer rewards contemplation?

One of the more unsettling developments unearthed in this sea change isn’t just that most Americans are reading less — it’s who still reads. A recent Fortune article points out a striking divergence: long-form reading remains a consistent, daily habit among the ultra-wealthy and powerful. Figures like Bill Gates, Oprah Winfrey, and other elite decision-makers openly credit daily reading with shaping their thinking, judgment, and long-term success.

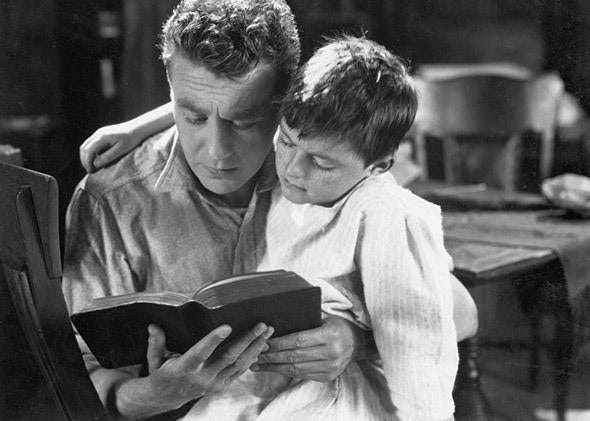

Reading hasn’t disappeared; it has concentrated. Fewer Gen Z parents report that they enjoy reading aloud to their young children. For many, it has become an obligation rather than a pleasure. This is how practices die: through indifference.

It would be easy to dismiss all of this as nostalgia or moral panic. Every new medium has triggered anxiety. Pulp fiction once corrupted youth, and television was supposed to rot their brains.

But this moment has a distinguishing feature: reading is no longer structurally necessary for participation in public life. You can be politically engaged, socially connected, and economically functional without ever reading a long text. That means reading now survives only if people choose to do it. And in a world as complex and fragile as the one we live in, it’s a choice few are making.

Collapse produces contradictory signals, incomplete information, and moral ambiguity. Navigating that terrain requires exactly the capacities that deep reading trains: patience with uncertainty, resistance to oversimplification, and the ability to reason across time rather than react in the moment.

Add to that the new fear that artificial intelligence is creating an alternate, holographic reality. Without the critical thinking skills that reading helps develop, it becomes more difficult to parse reality from hallucination. And if the printed word disappears from the culture all together by virtue of the laws of supply and demand, we’re left with nothing but 1s and 0s — endlessly editable, mutable, and ephemeral. Nothing is fixed or permanent anymore. What, then, will we store in the libraries of the future?

A society that scrolls rather than reads gravitates toward slogans. A generation trained on fragments grasps for certainty too quickly because it is unused to ambiguity. Certainty, in moments of systemic stress, is often the most dangerous thing being offered.

Reading has always been a form of escape, but it was also a way to immerse yourself in other people’s lives, other people’s futures or pasts, other people’s failures — without having to immediately act them out. In that sense, reading was a form of preparation.

Books won’t save us from whatever is coming down the line. But the habits that books once trained us on are exactly the habits a collapsing world demands.

Thought for the Day: We get the world we deserve, and apparently what we deserve is a world where most adults either don't read at all, or read only minimally.

Thought for Tomorrow: I'm always impressed with the thought-provoking essays presented at Collapse Life, and I'm very grateful for this content provided on that substack by writer Zahra Sethna. - BG

I have a library of at least 1000 books. I will pass them on to the next generation.