How the raid of a Portuguese merchant ship shaped the world we live in today

An excerpt from Collapse Life's first book: 'Hidden Histories,' just released on Amazon.

History doesn’t get forgotten, it gets managed. What we’re taught to remember is meticulously curated to simplify and strip down uncomfortable realities.

Our new book, a tight compilation of key historic events called Hidden Histories, was written as an act of recovery; a deliberate return to overlooked stories, suppressed knowledge, and inconvenient truths that help explain how we arrived here — and why so many of our present-day “crises” feel eerily familiar.

Today, we’re sharing the first chapter from the book, which is now available on Amazon.

The past is rarely as tidy as we’re told, and it has a habit of resurfacing when it’s ignored for too long. The full book goes into more detail, chronicling seven other episodes from history that you may or may not know about. We hope you’ll feel compelled to buy it and read them all. In fact, it’s bargain-priced at just $4.99 (hard copy), so you can read it, and then pass it along to others who might be interested. Collapse Life isn’t looking to become the next Dean Koontz or Tom Clancy.

The following chapter, which we share as a sample of what you can expect, should be enough to remind you of one thing: history leaves traces that we still live amongst.

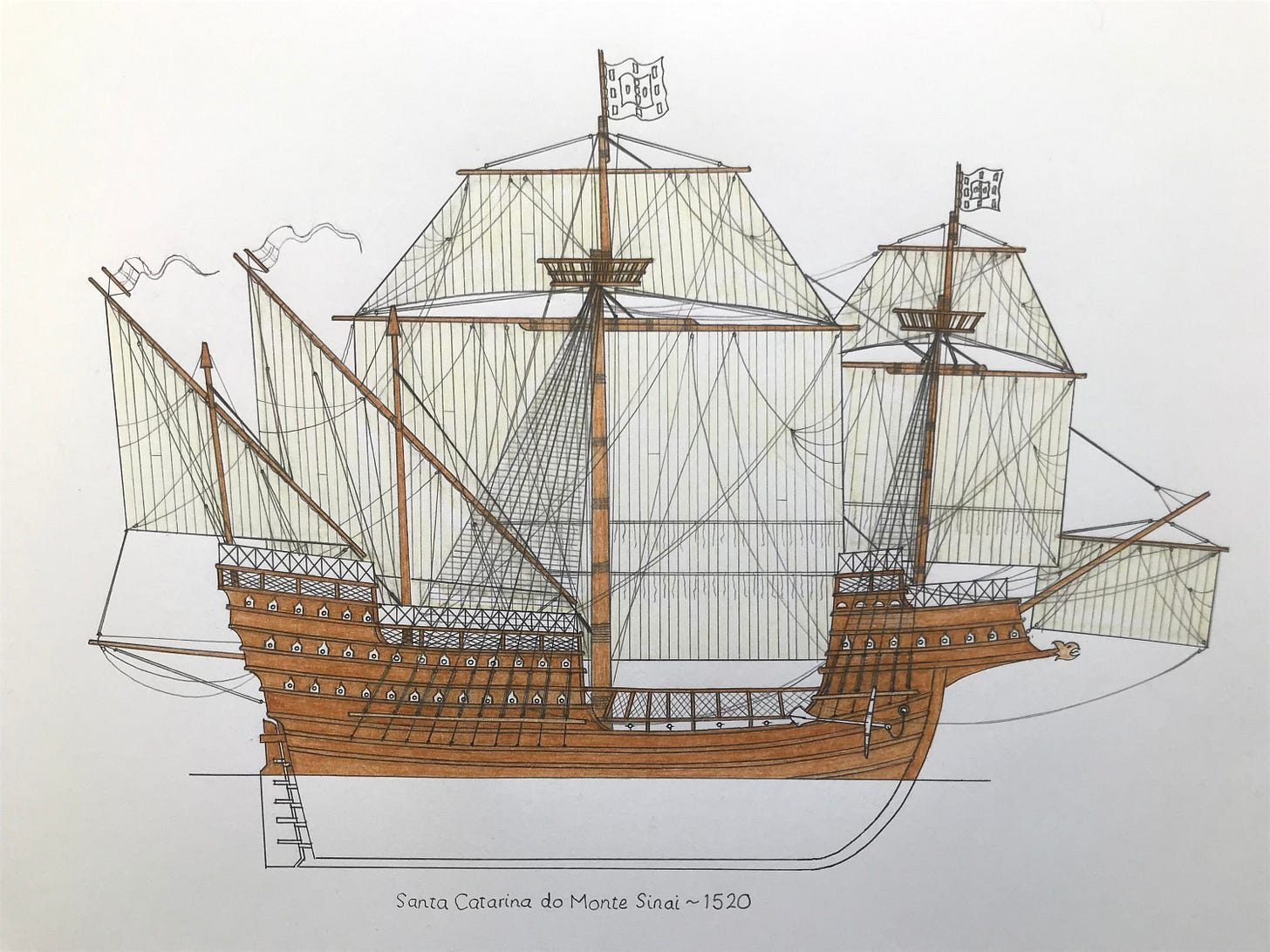

The dawn of February 25, 1603, revealed a prize beyond imagination to the crews of three Dutch ships anchored at the mouth of the Johor River, just off the Strait of Singapore. Overnight, the Portuguese carrack Santa Catarina had moored beside them. It was a towering, teak fortress weighing around 1,500 tons and packed with hundreds of soldiers and sailors, women and children, and captives bound for European slave markets. In her holds, the Santa Catarina held bolts of silks from China, spices from the Moluccas, musk from Tibet, and stacks of blue and white porcelain destined for elite tables across Europe.

At eight o’clock that morning, Jacob van Heemskerck gave his troops the order to attack. A seasoned Dutch admiral sailing under the banner of the newly formed Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC) — commonly known as the Dutch East India Company — he commanded his fleet with the confidence of a man who knew he carried the backing of a powerful new enterprise. Yet Van Heemskerck had no official privateering commission authorizing the assault. He cautioned his gunners to aim only at the ship’s mainsails — “lest we destroy our booty by means of our own cannonades.”

The Portuguese were unprepared for a fight; their broad-hulled carrack was built for cargo, not combat. The day-long clash was grim and lopsided, and by early evening the Portuguese captain, Sebastião Serrão, had surrendered.

The Santa Catarina was now Dutch property and with her, the spark had been lit for a legal and geopolitical shift that would forever reshape the seas.

To the Portuguese Crown, the attack was an act of piracy. To the merchants who ran the VOC, it was a windfall so massive it could fund years of voyages. But to one young Dutch lawyer, it was something else entirely: a legal puzzle to solve and an opportunity, largely unbeknownst to him at the time, to change the rules of the world.

In the early 17th century, the oceans were not “free.” They were parceled out like estates by the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas, in which Spain and Portugal — backed by papal authority — carved up the non-European world between them.

Portugal claimed a chain of fortified ports from Goa to Hormuz to Malacca, bottling up the Asian spice trade. Access to these routes was guarded by the cartaz system, a kind of maritime passport. Any ship sailing the Indian Ocean without a Portuguese license could be seized, its cargo confiscated, its crew enslaved.

The Dutch Republic, a young breakaway from Spanish Habsburg rule, wanted in. The spices of the East — nutmeg, cloves, mace, pepper — fetched astronomical profits in Europe, as did the silks and ceramics. But legally, by European custom, they had no right to break into Iberian waters without declaring open war, something the fragile Dutch state was reluctant to do.

The Santa Catarina’s capture changed that calculation.

Heemskerck’s prize was valued at over 3 million guilders, equivalent to half the Dutch government’s annual revenue at the time. The news electrified Amsterdam, where merchant capital was always on the hunt for a justification to turn risk into policy.

The problem was the seizure happened in neutral waters by standards of the time. Portugal and the Dutch Republic were not formally at war. If the seizure was declared unlawful, the spoils could be confiscated or, worse, forcibly returned.

The merchants from the VOC turned to a legal prodigy to craft their defense.

At age 21, Hugo de Groot, also known as Hugo Grotius, was already a legend in the Dutch Republic. Fluent in Latin by age 8 and admitted to university at age 11, Grotius moved easily between the worlds of law, theology, and diplomacy. While the VOC likely expected to receive a short legal pamphlet, Grotius produced a 500-page treatise titled De Jure Praedae (”On the Law of Prize and Booty”) to justify the seizure.

The full treatise remained unpublished until 1868. But one chapter in particular, Mare Liberum (“The Free Sea”), laid out his revolutionary solution. Grotius argued that the oceans were international commons — no nation could claim exclusive rights over them. In effect, Portugal’s claim to own the sea lanes to Asia was null and void. The Dutch, and by extension any nation, had the right to sail, trade, and fish anywhere on the open ocean. The seas, he said, were “as common as the air.” Thus, trade and navigation were natural rights granted by God and nature, not privileges to be parceled out by kings or popes.

This was more than a legal fig leaf to cover up for the capture of the Santa Catarina; it was a frontal assault on the Iberian monopoly system. The argument resonated beyond the case at hand, becoming a cornerstone of modern international maritime law.

But there was an irony built in: Grotius’s lofty principle of open seas was, in practice, a weapon for Dutch corporate expansion. “Freedom of the seas” meant freedom for the VOC to muscle into Asian trade routes and exclude others once it had wrested control.

Just a few years before the attack on the Santa Catarina, the Compagnie van Verre (more about it in a moment) dispatched a fleet of four ships to the East Indies under the command of merchant seaman Cornelis de Houtman. It was the first Dutch voyage to those waters.

The journey was brutal: of the 249 men who set out, fewer than 90 returned. Yet it proved two things — that a direct sea route to the East Indies was possible, and that the Dutch could take on the Portuguese monopoly.

The Compagnie van Verre was one of six small private East India companies that operated out of the Netherlands, each vying for a share of the lucrative spice trade dominated by the Portuguese. The rivalry between them undercut broader Dutch ambitions, as competition between them diluted resources and hampered the creation of a unified, profitable trading network capable of challenging Portuguese control.

To end the costly competition among the six companies, the States General — the Dutch Republic’s highest governing body — ordered them merged into a single joint-stock enterprise. In March, 1602, the VOC received a 21-year charter and 6.4 million guilders in starting capital.

In effect, the VOC was a state-mandated fusion of the “voorcompagnieën” (pre-companies) into one powerful corporate arm of the republic. This new entity could wage war, sign treaties, build fortresses, coin money, and govern territories in the name of the Dutch Republic — all while raising private capital through the sale of shares. It was the world’s first joint-stock corporation with tradable shares, and arguably the world’s first true multinational.

A new stock exchange emerged in Amsterdam to trade VOC shares and bonds. Investors could profit from voyages they never set foot on. Risk was pooled, rewards shared, and war became a line item in the corporate ledger.

The VOC perfected ‘vertical integration’ centuries before the term existed. It controlled every stage of the supply chain: growing spices in the Moluccas, transporting them on its own ships, warehousing them in Batavia (present-day Jakarta), and auctioning them in Amsterdam.

The Company’s enforcement arm was formidable: fleets of warships escorted convoys, private armies captured ports, and sieges starved rival settlements into submission. Its methods were unapologetically ruthless and the monopoly logic was merciless: destroy “illegal” spice trees outside its control, punish smugglers with death, and keep supply artificially low to drive prices sky-high.

In the Banda Islands of Indonesia in 1621, the Company massacred or enslaved most of the population to secure a nutmeg monopoly. In Java, it backed rival rulers against each other to fracture political unity and secure favorable trade terms. In its Cape Colony (which eventually became modern day South Africa), it imported slaves from Madagascar and the East Indies to build a settler economy that eventually outlasted the Company itself.

For all the romance that clings to the image of tall ships and exotic spices, the VOC’s business model ran on human suffering. It was a major participant in the Indian Ocean slave trade and a large-scale user of enslaved labor. Wherever it operated, the Company increased demand for slave labor, reshaping economies to serve export crops and breaking local self-sufficiency traditions.

The Company’s own size and power bred inefficiency. Its officials, paid poorly, turned to private trade and corruption. The Company often paid generous dividends, frequently financed by debt, which drained its capital — essentially a form of financial self-cannibalism. Wars with Britain, especially the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War (1780–1784), wrecked its fleet and weakened its Asian positions.

The VOC’s original 21-year charter from 1602 had been renewed multiple times, with the last renewal expiring in 1799. The Dutch state took over its debts and possessions.

However, while the corporate experiment had collapsed, its methods lived on.

The tangible legacy left by the VOC is harder to see than a ruined fort or a sunken ship’s bell. Its real legacy is systemic, and it survives in the idea that a company has legal rights separate from its owners, in multinationals that negotiate directly with governments, in trade agreements that override national laws, and in corporate security forces that guard mines and pipelines.

What started with the trading of VOC shares on Amsterdam’s fledgling exchange some 420 years ago still casts a long shadow in global capital markets, with integrated supply chains that allow for control of everything from production to distribution, and in maritime law as the basis for commercial dominance and warfare.

Grotius’s “free sea” concept remains a legal tool for securing trade routes, now applied to oil tankers, container ships, and even satellite constellations.

Today, Dutch politicians still speak of the “VOC mentality,” as Prime Minister Jan Pieter Balkenende did in 2006, referring to entrepreneurial daring, innovation, and global reach. What is left unsaid is the other half of that mentality: the readiness to bend law into a weapon, to treat foreign lands as markets-in-waiting, and to fuse public power with private profit.

Modern visions for a technocratic utopia — from Peter Thiel’s seasteading ventures to Balaji Srinivasan’s “network states” — draw on Grotius’s logic, repurposing the idea of a sovereignty-free space for digital governance and offshore finance rather than cloves and nutmeg.

The Santa Catarina’s seizure was more than a windfall. It was the moment when law was bent to fit commerce, and commerce reshaped the world. The oceans became an arena for private power cloaked in public principle. Four centuries on, the names have changed — from carracks to container ships, from nutmeg to lithium, from fortresses to data centers — but the operating system is the same.

We still sail in the VOC’s wake.

thanks for posting this. I'm Dutch born and raised, and I was already aware of my country being somewhat responsible for corporatism, and therefore (to a large extent) for the state of today's world . This piece fills in many of the blanks. It leaves me both proud and ashamed, if you know what I mean.

Off topic - Have you caught up with Ethical Skeptic and ECDO yet?