History repeating: the new company town

What happens when billionaires own the zip code, and everything within it? Part two in our series on the future of living in America.

During the Industrial Revolution, company towns sprang up across the United States like dandelions after a downpour. Built by steel tycoons, coal barons, and chocolate magnates, these places were designed to allow workers to live close to where they work — keeping them away from the denigrating poverty of inner cities, and keeping them under close watch.

Some versions were brutal: Kentucky coal towns like Lynch, for example, were notorious for housing miners in shacks with no plumbing and paying them in company scrip that could only be spent on overpriced goods at the company store. Others tried to pass as idyllic: Hershey, Pennsylvania had neat lawns, bowling alleys, and a chocolate-fueled amusement park. Corning, New York had museums and libraries courtesy of the glass company. Pullman, Illinois had stylish worker housing until the company slashed wages but kept rents high, sparking a nationwide strike.

What they all had in common was control. Workers lived where their bosses told them, bought what their bosses sold them, and behaved how their bosses expected. The message was clear: if you want a paycheck, you play by the rules. Sometimes, that meant waking up to factory bells at 4:30 in the morning and attending mandatory church service. Sometimes, it meant not striking, not speaking up, and definitely not trying to unionize.

The company town model was supposed to fade away with the rise of public infrastructure and labor rights. But it didn’t — it just got rebranded.

Today’s version comes with better marketing. The factory bells have been replaced with free yoga, wellness apps and solar panels. “Moral behavior” now means staying within the parameters of a 15-minute city or a biometric security fence. The new company towns don’t just expect conformity — they engineer it.

In this second part of a series on how billionaires are working to shape our lives, we look at the modern resurrection of the company town:

Starbase, Elon Musk’s handpicked city, governed by his employees and gated from the public.

Lāna‘i, a Hawaiian island once run by Dole Pineapple, now owned by one man.

Belmont, Bill Gates’ planned desert city built around data centers.

And Sidewalk Labs, Google's failed attempt to privatize (and surveil) a piece of the Toronto waterfront.

In all these cases, the model is the same: a private entity builds the world it wants, sets the rules, and invites you to live in it — on its terms, not yours. While the new company town may be smarter, greener, and more connected — it’s just as rapacious and controlling as ever.

Starbase, Texas is Elon Musk’s 21st-century company town built on a sandy strip on the Gulf of Mexico formerly known as Boca Chica Village. It began, like so many Musk projects, with a tweet. In 2021, he announced plans to build a city around SpaceX’s rocket launch site and soon began buying up houses in the once-quiet coastal village, turning it into a restricted zone for private launches, tourists, and security patrols.

Some locals resisted, calling it rocket fueled gentrification, but Musk pressed on and in early May 2025, Starbase officially became a city after what may have been one of the strangest elections in modern American history. No campaign signs, no public debates — just 280 eligible voters, most of them SpaceX employees or their relatives. Roughly 90% of them registered to vote within the past year, and most of them were young men. When ballots were cast, the city’s incorporation measure passed 212 to 6. The new mayor is a SpaceX vice president and all the commissioners are also tied to SpaceX. In Starbase, corporate loyalty is literally a civic requirement.

The company has wasted no time consolidating control. Just weeks after incorporation, Starbase moved to adopt sweeping zoning ordinances. Residents received legal letters that noted, in all-caps letters no less, “YOU MAY LOSE THE RIGHT TO CONTINUE USING YOUR PROPERTY FOR ITS CURRENT USE.” Many properties — some held for decades by families who came to fish, hunt, or retire in peace — are now designated as "Mixed Use," "Heavy Industrial," or "Open Space."

The letter informed recipients of a public hearing, which took place this past Monday, June 23, 2025. About 80 people showed up to voice their confusion and anger and ask why they were being strong-armed into new zoning rules they didn’t understand. Some asked how their property rights would be affected, or whether SpaceX might use eminent domain. The city attorney denied it — “not what this is,” he said — but to landowners who feel outnumbered and outmaneuvered, the writing’s on the wall. If SpaceX doesn’t own your land yet, it wants to control what you can do with it. One local said he felt “like a Native American, because these people are coming in… making their rules, and it’s a done deal, basically.” Another expressed amazement at the new map the city is proposing. “Have you seen it?” he said. “It looks like a spider web on LSD.”

And then there are the gates.

Citing “security concerns,” and “folks who aren’t necessarily here for the right reasons,” the city commission — staffed by SpaceX employees — approved the installation of four gated checkpoints, turning formerly public roads into controlled-access zones. Some gates were completed before the vote even took place, raising questions about whether the company was simply rubber-stamping its own decisions after the fact.

“That is a travesty,” said Mike Montes Jr., who attended the June 23 meeting. “I think they are trying to have a private interplanetarian community.”

Officials say residents will still be allowed in and first responders will get access codes. Visitors can be “screened.” But critics — including property owners and even the local district attorney — say blocking public roads violates Texas law.

Meanwhile, Starbase is operating on borrowed money — literally. The city took out a $1.5 million zero-interest loan from SpaceX to fund its startup budget through September 2025. No sales tax. No property tax yet. Just corporate credit from the only business in town.

If this all sounds a bit dystopian to you, you’re not wrong. Starbase is not the techno-utopia it pretends to be. It’s a municipal Halloween costume for a rocket company that wants legal cover to control land, people, and infrastructure without state interference. It's also a legal loophole: by incorporating as a city, Starbase gains more power to shut down roads, access public funding, and operate with municipal authority — all without any meaningful democratic input.

This is not Musk’s first foray into privatized governance. He’s floated plans for Mars colonies governed by “direct democracy” — a term that sounds egalitarian until you realize his company will also own the oxygen supply. Starbase is, therefore, the test site for more than rockets. It’s a dry run for post-national corporate rule.

Then there’s Lāna‘i, Hawaii. If Starbase is a company town for the 21st-century, Lānaʻi is its mirror image: a place steeped in company-town tradition, now rebooted by one of Silicon Valley’s richest men. Once dominated by pineapples, Lānaʻi is a living case study in how private ownership of public life mutates with the times — and why it still matters.

Purchased in 1922 by pineapple magnate James Dole, Lānaʻi quickly transformed into the world’s largest pineapple plantation and a textbook example of a model company town. Dole built not just the fields and packing houses, but also Lānaʻi City — the central town with a movie theater, a park, and homes for thousands of workers and their families. But this was no tropical utopia. As with many plantation towns, workers toiled long hours, earned little, and lived in housing owned by the same company that employed them. Dole controlled the economy, infrastructure, and much of daily life — and when the pineapple business dried up, so too did the island’s economic base.

That is, until another tycoon came along.

In 2009, the island was included on the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s list of America’s most endangered historic places. Three years later, in 2012, Oracle cofounder Larry Ellison bought 98% of the island for $300 million. The purchase included two Four Seasons resorts, the water utility, much of the housing, the community pool, and even the island’s movie theater. And in 2019, Ellison added one more asset to his collection: Lanai Today, the island’s only newspaper.

That’s right — the billionaire landlord is now also the publisher of the local press.

Ellison has remade Lānaʻi in his image: a wellness-focused, ultra-elite retreat where tourists arrive on private jets, dine at Nobu, and soak in curated luxury. At the same time, residents live in what critics call a "plantation 2.0" system. They work at Ellison’s hotels, rent homes from his holding company, shop at his grocery store, and read his newspaper. And while many residents express gratitude for Ellison’s pandemic generosity — he waived rent and kept people on payroll — others say the cost is quiet compliance.

Maui County Councilman Gabe Johnson put it bluntly: “This is still a plantation town, it’s a one-company town. To speak out in public, there’s risks involved for anyone.”

Residents who speak up about housing shortages, shrinking public services, or the mysterious drone testing project have to weigh those complaints against their livelihood. For many, Ellison is their landlord, employer, infrastructure provider, and de facto government. Dissent becomes a gamble.

Ellison claims he wants to turn Lānaʻi into a model of sustainability — powered by hydroponic farms, Tesla solar panels, and “an adults-only, luxurious wellness enclave.” But critics note that sustainability in this context often means control: of food, housing, jobs, and now, information.

[As an interesting aside, that previously mentioned drone project involves assembling and shipping giant unmanned drones called Hawk30, which have a wingspan of 260 feet and a cruise speed of nearly 70 miles per hour. Propelled by 10 electric motors and onboard lithium ion batteries, the drones are designed to carry 5G transmitting equipment for up to 6 months at about 65,000 feet in the stratosphere.]

Meanwhile, housing on Lānaʻi is tight and what little is available comes with sky-high rents. As of mid-2025, only about two dozen homes are available for sale — ranging from $315,000 for a 400 square foot condo to $17 million for an 8,500 square foot, 7-bedroom mansion.

Ellison’s defenders say he saved Lānaʻi from decline. He fixed the pool. He restored the movie theater. He preserved the resorts. But these efforts, while real, come with a catch: centralized ownership of nearly every lever of island life. In a place with just 3,000 residents, there’s no anonymity — and no public space truly free from the touch of Ellison’s empire.

From Dole to Ellison, Lānaʻi remains a study in soft coercion — where power is quiet, but absolute. If modern technocracy demands centralized data, urban control, and seamless citizen management, Lānaʻi may be its testbed. But unlike NEOM’s mirrored city or Telosa’s blueprint fantasy, this one already exists.

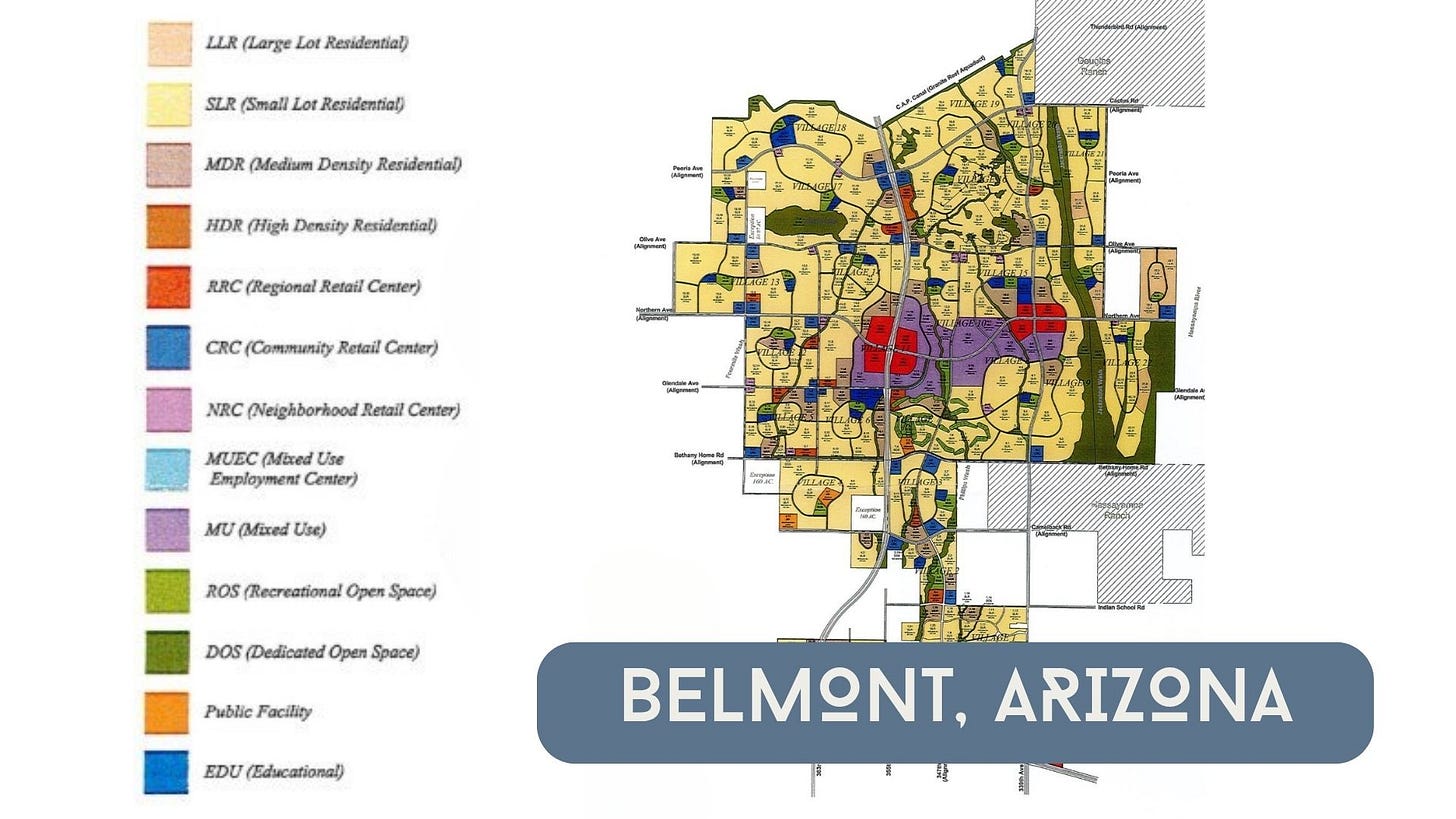

Belmont, Arizona, Bill Gates’ desert experiment, hasn’t even broken ground yet. Back in 2017, Gates quietly bought 24,800 acres of land west of Phoenix through his investment firm, Cascade, for $80 million. The plan is, by now, pretty obvious: Build a smart city with autonomous vehicles, sensor-stuffed homes, and traffic systems that think faster than you do. If it ever happens, the city will support 80,000 homes, 3,800 acres of industrial and office space, 470 acres for public schools, and enough infrastructure for around 180,000 people.

Nearly a decade later, Belmont remains an empty stretch of sand baking under the Arizona sun with no construction, no water, and just the vaguest promise that if you build a city around the internet of things, the people will come.

Perhaps Gates is wary of making the same mistakes Sidewalk Labs made when it set out to build the future of cities on Toronto’s waterfront. It had the backing of Alphabet, the parent company of Google, and a willing partner in Waterfront Toronto, a government agency responsible for redeveloping the lakeshore. But three years later, the $900 million project collapsed under its own weight — before a single shovel hit the ground.

On paper, Sidewalk Toronto offered all the usual utopian trimmings: heated sidewalks, robo-taxis, underground waste collection, dynamic buildings that shifted with the hour. But that was just the surface. Underneath was a far more radical proposition: to remake not just infrastructure, but governance. Data collection would be ubiquitous. Public systems — transportation, waste, energy, even benches — would be managed by software and sensors, with Sidewalk Labs at the helm.

That’s where it lost the public.

From the start, Toronto residents asked hard questions. Who would own the data? Who would make the rules? What kind of city turns public life into a private dataset? Sidewalk’s answers came too late — and rang hollow. The public wasn’t just wary of surveillance, they were wary of a tech company writing the rules of city life behind closed doors.

Waterfront Toronto tried to negotiate better terms, but it didn’t have the legal or political authority to manage what was, essentially, a transfer of public power to a private actor. The project wasn’t just a land deal — it was a Trojan horse for privatized governance.

And Toronto, in the end, said no.

This matters, because other companies are trying again elsewhere. Meta wants to build Willow Village in Menlo Park. Google has designs on Downtown West in San Jose. Each promises to solve the urban problems governments have failed to fix — housing, transit, climate — with data and design.

But if they don’t learn from Sidewalk Labs, they’re doomed to repeat its failure.

If you missed part one of this series on how the wealthy elite are planning our future, click below.

Thanks for this very informative article.

Good articles, have or will be linking both at https://nothingnewunderthesun2016.com/

This all a part of Agenda 2030 and how they get people into Smart Cities.