There is no 12-step program for America’s addiction to cheap stuff

For decades, globalization has allowed us to live like emperors, but the era of endless bargains was built on hidden costs. Now tariffs are shattering that illusion.

Picture, for a minute, life from a banana’s point of view.

Before dawn, a man with a machete cuts your stem in a field that looks more like a factory. You’re hauled to a tin shed, dunked in chemicals, slapped with a sticker, boxed and stacked six feet high. A flatbed rattles you to a port, where refrigerated containers swallow whole pallets of your kind. On the ship, sheer volume works its magic: millions of pounds of bananas moving at once make the cost of the journey fractions of a penny per fruit.

At the next port, cranes whisk you onto trucks bound for a sealed ripening room where a dose of ethylene gas jolts you awake at just the right moment. You shift from green to yellow on cue, primed for a three-day stint under fluorescent lights. In the supermarket, you’re displayed at the entrance, with a sign board priced at 20 cents. As a lost leader, you signal to the shopper that this store offers good value. You may bruise or rot before anyone buys you, but that’s part of the plan. Your low cost is subsidized by the steak, olive oil, and bottle of wine that leaves with the shopper.

That’s the visible chain, of course. The invisible one is longer. And more sordid.

Soil stripped by chemicals; Rivers laced with runoff; Workers trapped by economies bent to export agriculture; Cargo ships exhaling exhaust into the skies; And energy grids bear the weight of ripening rooms. The true cost is seen everywhere but the price tag.

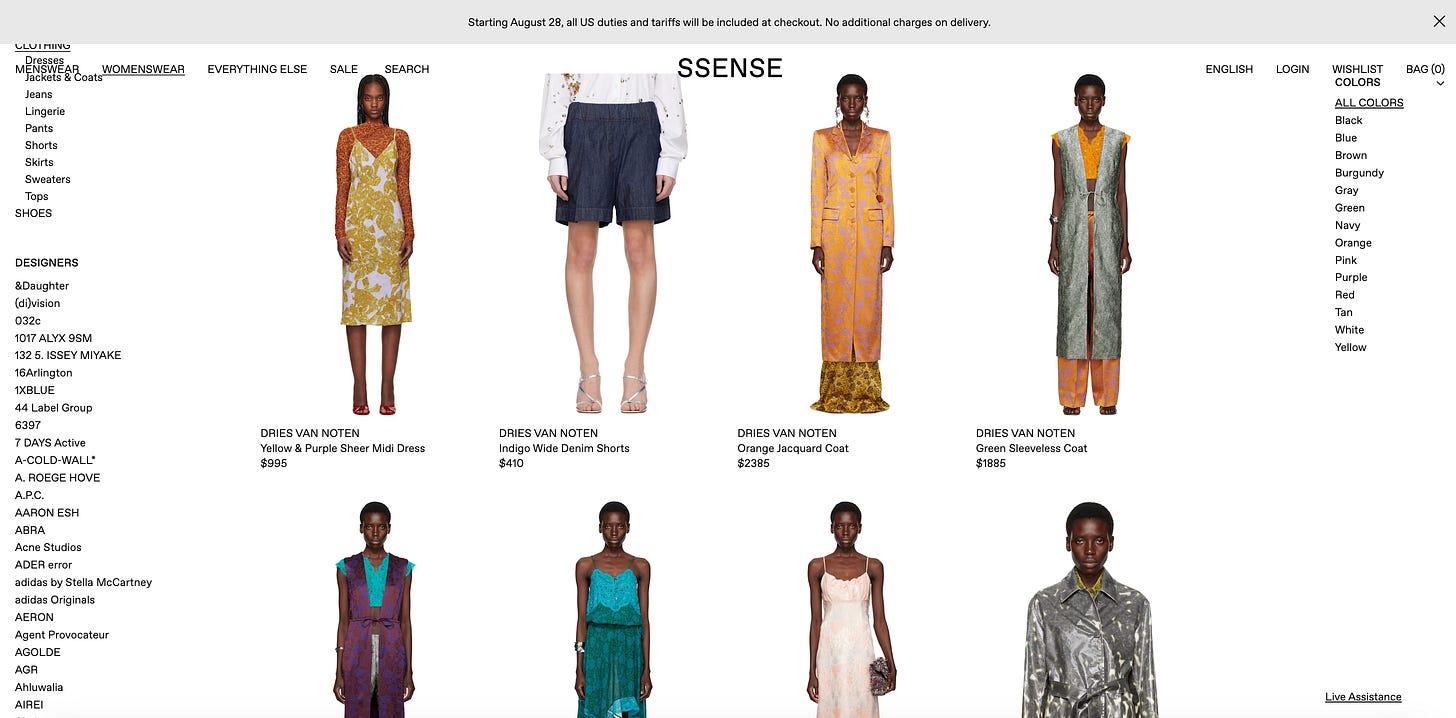

That’s the low end of the miracle of globalization. The other end is illustrated perfectly by a recent anecdote from author Susan Orlean, who tells the story of ordering designer clothes online for an upcoming book party. Designed by a Dutch label, made in Italy, purchased from a boutique in Canada, her order took forever to arrive. When it finally did, the US Postal Service slapped her with a bill for more than $2,000 in tariffs.

Bananas at 20 cents and designer outfits with $2,000 surprise fees are, surprisingly, the same story with different packaging.

Globalization was sold to the world as a necessary good. In the 1990s and early 2000s, we were told it would reduce poverty, make products affordable, and bind nations together in a seamless web of prosperity. Economists celebrated the way a T-shirt could be stitched in Bangladesh, shipped to Europe, sold through a British reseller, and worn in Chicago — all while lifting the Bangladeshi worker out of extreme poverty.

To be fair, globalization did reduce poverty in many parts of Asia, but it also hollowed out American factory towns, concentrated wealth into the hands of multinationals, and hooked consumers on the illusion of low prices. Walmart aisles and Amazon Prime deliveries taught people that “cheap” was normal and “instant” was their birthright. Few wanted to hear the protestors in Seattle in 1999 who shouted that the global trading system was built on exploitation.

For a while, the math of globalization held. Tariffs were low, shipping was frictionless, and the hidden costs were invisible. Americans learned to expect strawberries in winter, flat-screen TVs for a few hundred bucks, and throwaway wardrobes that could be replaced every season. And Bangladeshis enjoyed economic growth through job creation born from global supply chains.

But the bill was always going to come due.

When supply chains started to wobble during COVID, we collectively held our breath, then brushed it off as a temporary hiccup when things went back to the way they were before. Now, though, the brittle system is faltering again, as it was always bound to do.

One small business owner commented to Susan Orlean that his business is in trouble because he can’t get Latvian T-shirts into the country anymore. Another says she owns a Canadian business with an Etsy shop that does 75% of its business in the USA — “I’m essentially out of business,” she says.

Not to be unkind, but didn’t these entrepreneurs have contingencies built into their business plans? Their outrage, and the reactions of many others, is predictable and telling at the same time. American consumers are furious because they have been trained to believe cheap is normal. Small retailers are furious because their market of American consumers ready to buy cheap goods is no longer accessible. Everyone sees tariffs as theft, rather than correction. They see scarcity as an insult, not a reckoning. They need someone to blame and Donald Trump is the perfect bogeyman. If it weren’t for him, maybe we could keep on buying cheap stuff forever?

It’s hard to look the truth in the eye without facing our own role in the whole story. Globalization just exported scarcity onto foreign workers, foreign lands, and future generations, and now scarcity is being repatriated. Whether we have a President Trump now or a President Ocasio-Cortez in the future, the predatory and precarious system is destined to unravel at some point.

Here’s where the story mutates. The same people who once preached abundance through globalization now want restraint through globalism. Gone are the promises of endless goods; now the solution is to reduce the population, control everyone’s behavior, surveil citizens all day long, and enforce austerity in the name of the climate. You can have your bananas and cheap sneakers, as long as you accept rationing, tracking, carbon credits, stablecoins, and a digital leash. The very dependencies that globalization created have now become the perfect levers of control.

So what’s the answer? Do we stop eating bananas, drinking coffee, and buying beautiful clothes? Not exactly. The point isn’t to abolish pleasure, but rather to recover a sense of perspective. Preparing for de-globalization is about retraining the imagination. Bananas don’t have to vanish, but we should start to see them as a treat rather than a daily entitlement and recognize what it took to put them on your shelf. Coffee doesn’t need to disappear, but we may need to cherish one delicious cup a day instead of downing three disposable lattes with whipped cream on top. Clothes don’t need to be plain and joyless, but they should be bought with the understanding that nothing is ever truly “cheap” and that the large majority of fast fashion ends up in landfills. They used to call them ‘Sunday best’ for a reason.

From bananas to Balenciaga, the bill has now come due. The question is whether we pay it with panic or with grace. If you can picture a world where some things are scarce, others are seasonal, and very little is disposable, you’re already closer to resilience than your neighbor who freaks out when the bread aisle goes empty.

The world won’t end if you drink one coffee instead of three or if bananas become a rare treat. What will end is the delusion that everything can be yours, always, at a price that someone else has to pay.

Hidden costs are widespread I'd say and not just monetary costs. There are environmental and health costs. If a company can pollute or degrade something and by doing so make a profit what would stop them? We see it everywhere but it's brushed off or ignored because money talks if you know what I mean. Profit based systems have momentum and it's backed and fortified by our whole society. But look where it's headed now in our crazy world. For too long we've allowed profit to overrule responsibility and accountability, in agriculture, healthcare, energy, and the whole economy. The Earth is being ruined because we haven't come to terms with this yet.

Powerful stuff and there is a lot we the consumers can do , but the tariffs are a tactic of distraction. I listened to a talk about how Musk and many others get round the tariffs , including the setting up of “free trade zones “. It is all part of the con.

“It would be good for us to appreciate more of what the actual cost of cheap actually is..

If you can picture a world where some things are scarce, others are seasonal, and very little is disposable, you’re already closer to resilience than your neighbor who freaks out when the bread aisle goes empty.”